The world is drowning in money, yet for many, salaries barely cover the basics. Where does it all go? Why are salaries becoming thin each year? And who’s printing new money that keeps the system spinning? The answers might surprise you. Here’s what I found.

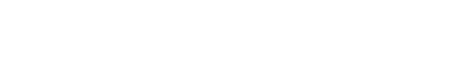

Money flow starts in the hands of people to purchase goods like food, medicine, and clothes. As these purchases happen, money flows to the companies that offer them. So, what about taxes and financial services? For the system to run smoothly, governments provide law enforcement, security, and oversight in exchange for taxes. Meanwhile, banks and payment companies facilitate loans and payments in exchange for interest and transaction fees.

When companies are acquired or pay dividends, money then flows to asset owners. These owners include various types of investors like entrepreneurs, investment funds, and individuals who purchase stocks or properties. This is where the majority of the money supply accumulates over time. See the image below for the flow of money from people to companies and asset owners.

Companies and entrepreneurs that deliver the most valuable products amass more wealth than anyone else, and so do the investors who support them. This dynamic is clear in the real world: in 2025 alone, giants like Google, NVIDIA, and Apple generated over $1 trillion in revenue, while their investors enjoyed soaring stock prices.

Over time, the majority of the economy’s money becomes concentrated in the hands of these companies and asset owners, leaving the broader population increasingly sidelined. To prevent economic stagnation, governments continuously inject new money into the system. Without this, economies stall because less money means fewer purchases, shrinking earnings, and weaker investment.

Money Printing and Inflation

Today, printing money is entirely digital. Central banks purchase bonds from private banks with just a few clicks, instantly injecting fresh funds into their reserves. These banks then lend that money to individuals and businesses, circulating it throughout the economy.

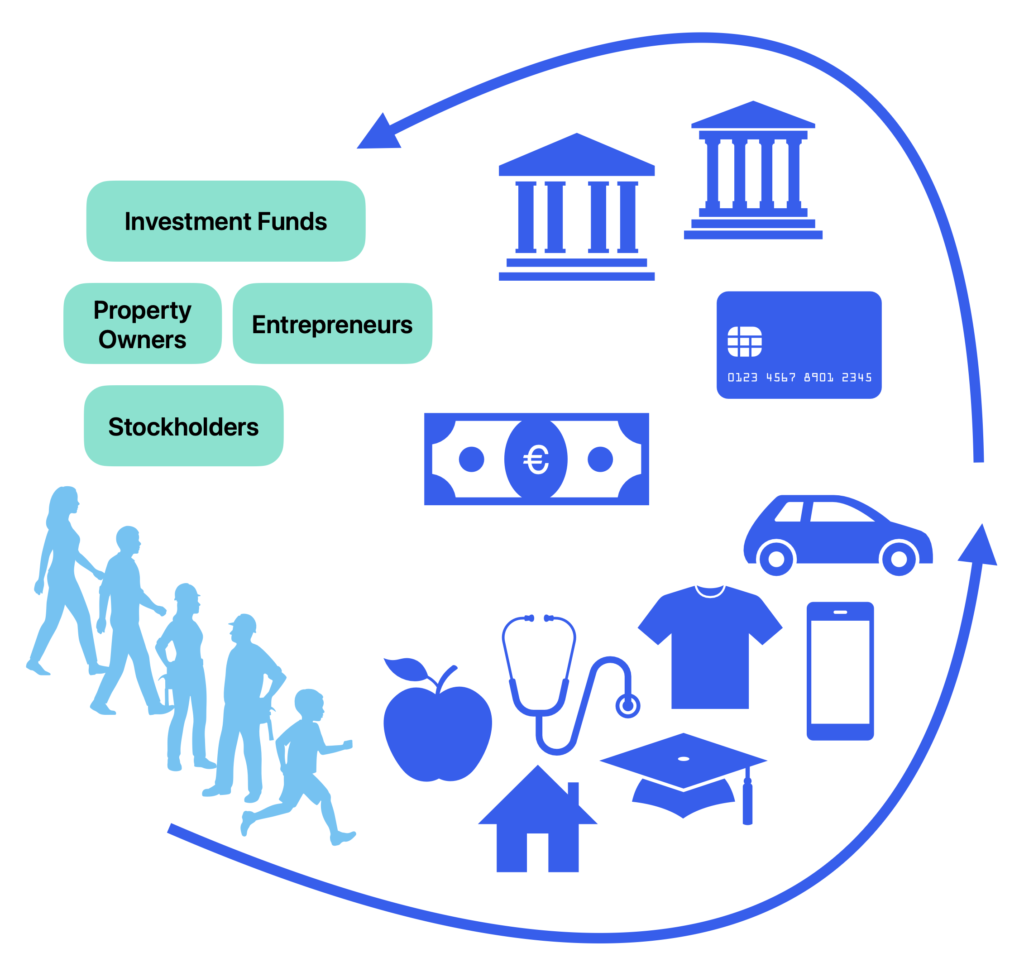

As this new money enters the system, demand for goods and services increases, pushing prices upward, causing inflation. Governments accept inflation as a necessary trade-off to stimulate economic growth. However, the downside is evident: as prices rise, the purchasing power of people’s money erodes. Also, wages rarely keep up with inflation, leaving many able to afford less than before,.

Think of our economic system as a hot-air balloon. The government’s money printing acts like the flame that keeps the balloon floating, while the money flowing inside represents the air within. Without continuous money creation, the system would deflate and stagnate. Just as a hot-air balloon has a narrow base and a wide top, money printing tightens the squeeze on those at the bottom, who lack assets, with higher living costs and sluggish wage growth. Meanwhile, companies and asset owners at the top continue to expand as newly printed money flows upward through the system.

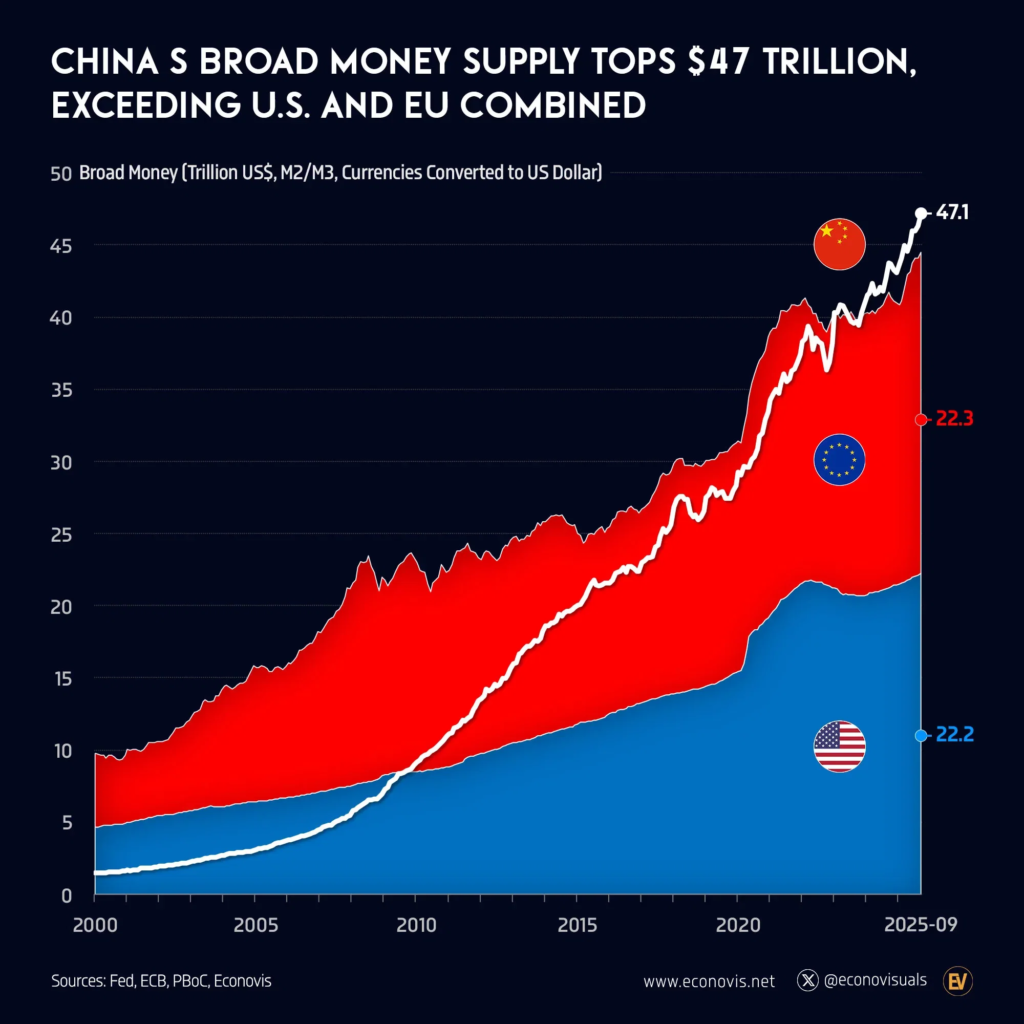

In practice, China, the European Union, and the United States are the world’s biggest money printers, and they also happen to be the three largest economies globally. As liquidity floods the system, capital inevitably concentrates in the hands of companies and investors behind the highest-value products. European countries attempt to counteract this trend by imposing higher taxes and heavily investing in social services. However, Europeans still face rising costs and slower wage growth.

It’s essential to recognize that simply increasing the money supply does not automatically lead to higher economic growth. For growth to occur, companies must produce high-value-added goods and services. For example, while China has expanded its money supply more aggressively than both the U.S. and Europe combined, it has yet to surpass their economies in terms of GDP. Additionally, China’s monetary expansion serves a strategic purpose: devaluing the yuan to boost Chinese exports.

A World of Debt and Extreme Measures

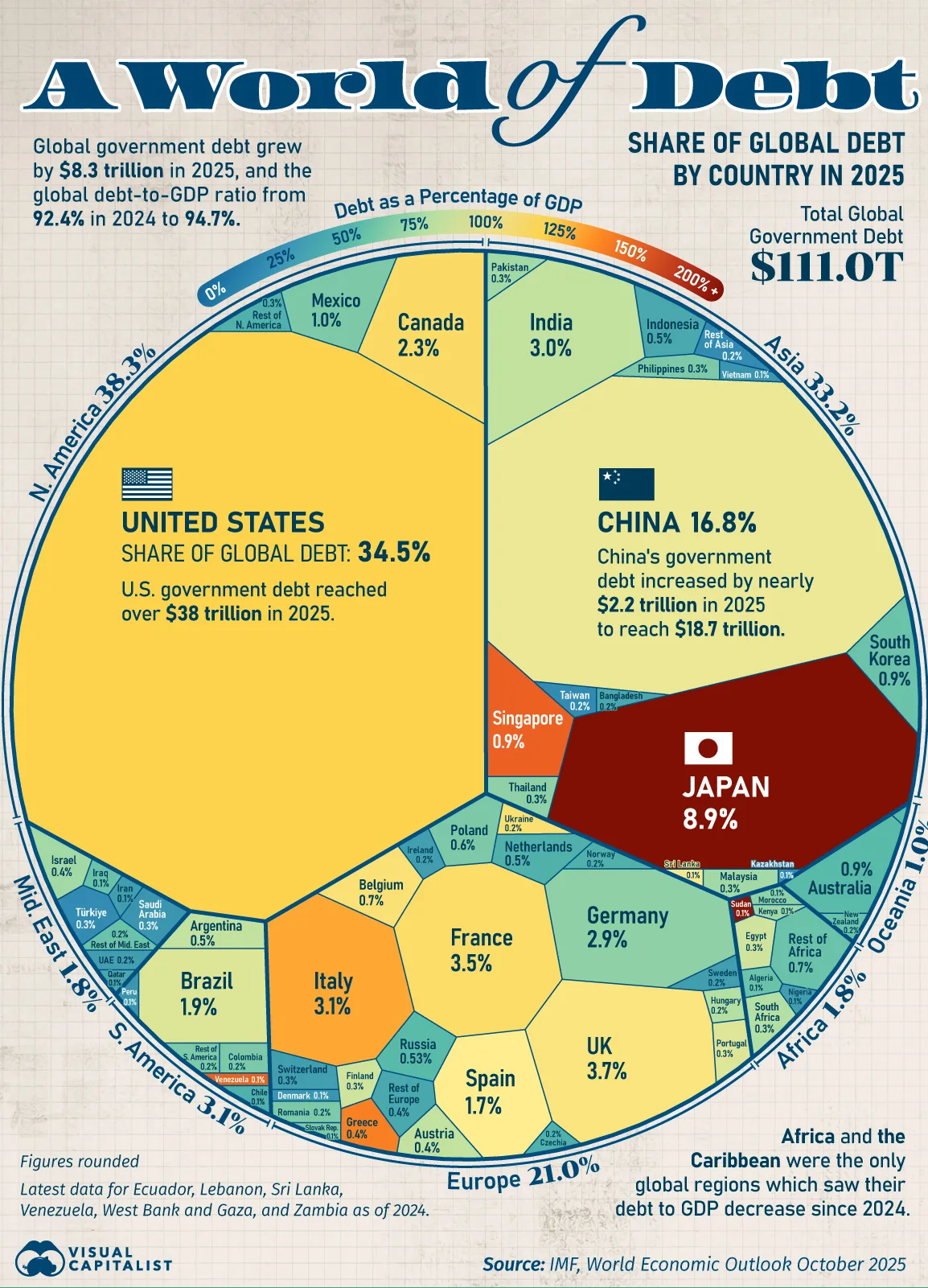

Inflation is a deliberate tool governments use to stimulate economic growth and reduce the real cost of government debt, making repayment more manageable over time. However, the current challenge is that global debt is so massive, a whooping $111 trillion, that paying it off is no longer feasible. See the image below with the total global government debt.

As shown in the image, U.S. debt reached $38 trillion in 2025. As the world’s largest government, the U.S. faces annual interest payments of $1 trillion. With debt at this scale, the only way forward is to consider extreme measures. The U.S. president is desperately exploring strategies to prevent government bankruptcy while maintaining steady inflation and improving affordability. These strategies include:

- Encouraging asset ownership by providing investment accounts for newborns and incentivizing the public to invest.

- Boosting GDP growth by prioritizing strategic industries—purchasing private company stocks, enacting legislation to support new technologies, imposing tariffs on imports, and lowering interest rates for investment loans.

- Expanding the money supply (via quantitative easing) to weaken the dollar against foreign currencies, thereby increasing the competitiveness of U.S. made exports, similar to China’s approach.

The most extreme solution to the massive government debts would be a complete reset of the monetary system, replacing it with a new standard. History shows this isn’t unprecedented, devalued currencies have been abandoned before, with economies reverting to gold standards until a new dominant currency emerges. This was the case for:

- The Byzantine Empire (5th–15th centuries): Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, the Byzantine solidus, a pure gold coin, became the backbone of Mediterranean trade for nearly 700 years. Its stability and widespread acceptance made it the ‘dollar of the Middle Ages,’ proving that gold-backed systems can outlast political fragmentation.

- Spain during (16th–17th centuries): The influx of New World silver initially fueled Spain’s economy but led to excessive inflation and repeated currency devaluation during the Price Revolution. When silver flows declined, Spain’s attempts to revert to stricter metallic standards failed due to persistent wars and debt, coinciding with the decline of the Spanish empire.

- Britain (1819–1821): After decades of paper money and wartime inflation after the Napoleonic wars, Britain returned to the gold standard with Peel’s Bill, restoring confidence by making banknotes convertible to gold. This reset was unique because it marked a deliberate, phased return to metallic money after a prolonged period of fiat currency.

The most recent global monetary resets occurred in the United States between 1944 and 1971, beginning with the Bretton Woods system, which pegged the U.S. dollar to gold from $20.67 to $35 per ounce. This devaluation resulted in an overnight loss of about 35% in purchasing power for foreign currency holders and U.S. debt holders. That system persisted until 1971, when President Nixon suspended gold convertibility, marking the transition to today’s fiat currency system.

The next potential monetary reset to a gold standard could unfold through gold-backed cryptocurrencies called “stablecoins“, such as Tether Gold (XAUt) or Pax Gold (PAXG). These digital assets represent a modern 21st century twist on the gold standard, as their parent companies match them with the value of gold by purchasing equivalent amounts of physical gold and storing them in vaults worldwide. While I’m not advocating for any specific investments, it’s worth noting how blockchain innovation is reshaping the future of money, and where the global economy is headed.

Regardless of how the global monetary system evolves, diversifying into assets like gold and silver remains a timeless strategy, whether buying them physically or digitally with ETFs, or stablecoins. Central banks and institutional investors are already signaling this shift, accumulating record levels of precious metals. Given these trends, we may well be witnessing the early stages of a new monetary paradigm, where digital gold and traditional hedges define the rules of the system.

There is Hope

The story of money is a story of trade, innovation, and politics. From gold-backed systems to digital currencies, every monetary system has winners and losers. Whether you’re in a neoliberal economy or a socialist one, the rules aren’t written in stone. The question isn’t whether the system will evolve, but how ready you are to position yourself for it.

For those willing to learn, diversify, and take ownership, whether through assets, skills, or strategic investments, the opportunities are real. Governments may print money, but you can print your future by investing in assets (real estate, stocks, and gold), leveraging technology to stay ahead of the curve in your job, and building multiple income streams to break free from slow growing wages.

As we stand on the brink of another monetary evolution, the future is yours to shape.